Explore the link between uveitis and SpA

SpA=spondyloarthritis.

Uveitis is an intraocular condition that occurs when the middle layer of the eye, the uvea, becomes inflamed.1

The pathogenesis of uveitis is driven by genetic predispositions, environmental factors, and immune responses.2 Uveitis is a common extra-articular manifestation of SpA, which includes axSpA and PsA.3 Understanding the shared pathobiology of these conditions can help guide management.

axSpA=axial spondyloarthritis; PsA=psoriatic arthritis.

Consider the causes and impact of uveitis

Uveitis can be driven by autoimmune response, infections, or idiopathic origins. There are many ways to classify uveitis, including as noninfectious (usually autoimmune-related) or infectious.1,2

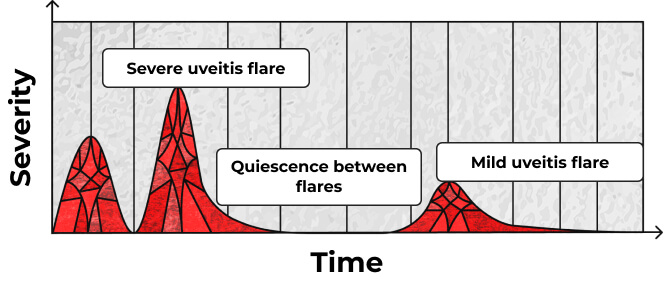

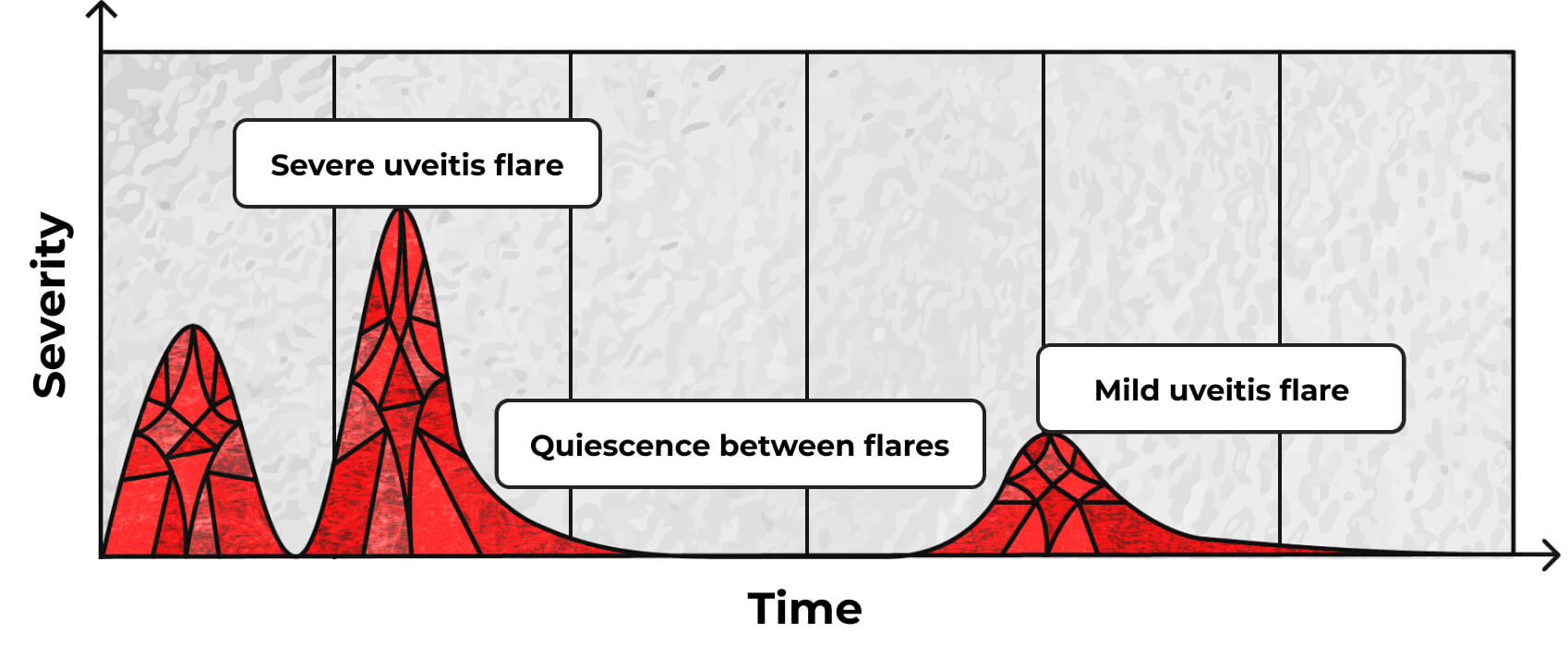

Uveitis can also be characterized by its onset and disease course. The onset may be sudden or insidious.4 The disease course may be acute, chronic, or recurrent. Acute uveitis is classified by sudden onset and limited duration, versus chronic disease where relapse occurs <3 months after discontinuing treatment. Recurrent uveitis is defined as repeated episodes separated by periods of inactivity in the absence of treatment for 3 or more months.4

Drug-induced uveitis

In rare cases, noninfectious uveitis may be induced by medications (drug-induced uveitis).5 Medications associated with uveitis include systemic medications, topical medications, intraocular drugs, and vaccines, making it important to monitor for symptoms of uveitis during use.5

Reflect on the possible diagnoses of uveitis

Uveitis can affect different parts of the eye, with the following diagnoses:

Artistic representation; does not reflect actual anatomy.

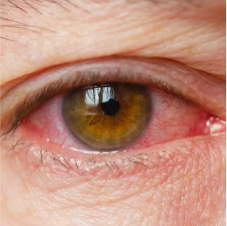

Panuveitis

Panuveitis is inflammation throughout the eye, affecting the anterior chamber, vitreous, retina, and/or choroid.7

Symptoms of panuveitis may include1:

- Eye pain

- Red eye

- Photophobia

- Blurred vision

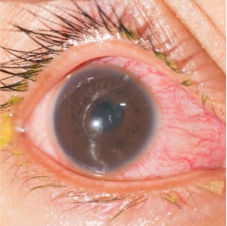

Anterior uveitis

Anterior uveitis affects the iris and/or ciliary body.1

Acute uveitis is classified as sudden onset with limited duration (≤3 months).4

Acute anterior uveitis (AAU) is the most frequent extra-articular manifestation of SpA.3

Symptoms of AAU may include4:

- Eye pain

- Red eye

- Photophobia

- Blurred vision

Intermediate uveitis

Intermediate uveitis affects the pars plana and peripheral retina.1

Symptoms of intermediate uveitis may include6:

- Blurred vision

- Floaters

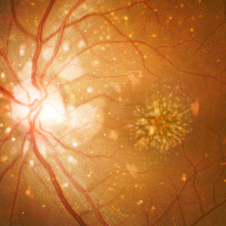

Posterior uveitis

Posterior uveitis affects the choroid and/or retina.7

Posterior uveitis may be asymptomatic, or symptoms may include1:

- Blurred vision

- Visual distortion

AAU may recur over time4,8

Patients may experience single flares or episodic and recurrent attacks.8,9

Patient burden of uveitis

-

Vision loss

- Uveitis accounts for up to 10% of vision impairment in the Western world1,10,11

- Recurrent AAU may lead to glaucoma, cataracts, and significant vision loss11

- Delayed treatment of AAU may result in glaucoma or severe visual impairment1,8

-

Quality of life

- Loss of vision resulting from uveitis is associated with significantly reduced quality of life12,13

- Uveitis can have negative impacts on general health and functioning, including relationships, bodily pain, physical functioning, and social activities12-14

-

Impact of gender

- Women more often have insidious rather than sudden-onset uveitis, and may be more likely to have frequent attacks of recurrent inflammation that require longer treatment compared to men15

- Men are more likely to develop spondyloarthropathy-associated uveitis, specifically HLA-B27–associated AAU, than women15

AAU can be found in ~30% of patients with SpA3

AAU is the most frequent extra-articular manifestation of SpA, affecting an estimated 21% to 33% of SpA patients.16,17 AAU can be the first presenting symptom that leads to a diagnosis of SpA.16 Longer duration of SpA is associated with greater risk of AAU.17,18

Prevalence varies within SpA disease types. AAU is more common in patients with AS (up to 33%) than in PsA (25%) or undifferentiated SpA (13%).16,19

Among the clinical phenotypes of SpA, the highest frequency of AAU occurred in patients with IBD (33%), followed by patients with enthesitis (23%), axial disease (22%), peripheral articular disease (19%), dactylitis (19%), and psoriasis (13%).18

PsA has been bidirectionally linked with uveitis, with PsA patients at higher risk of developing uveitis, and patients with uveitis at higher risk of developing psoriatic disease.20

AS=ankylosing spondylitis; IBD=inflammatory bowel disease.

Learn more about the extra-articular manifestations of inflammation

The HLA-B27 connection

AAU and SpA have both been associated with HLA-B273,16,18,21

The HLA-B27 gene, which is strongly associated with SpA, also increases risk of AAU.3,16,18,21

HLA-B27 positive SpA patients have a higher rate of AAU compared to those who are HLA-B27 negative (40% vs 14%, respectively).16 In patients who are HLA-B27 positive, AAU is more common in axSpA than PsA.16

Patients with AAU, especially those who are HLA-B27 positive, should be questioned about inflammatory lower back pain and evaluated for other clinical features of SpA, as AAU is often an early sign of undiagnosed SpA.16,21 One study showed a high percentage of HLA-B27 positive patients with idiopathic recurrent AAU without features of SpA have enthesis lesions comparable with those seen in SpA, suggesting that these patients may have an incomplete form of SpA.22

HLA=human leukocyte antigen.

The link between uveitis and enthesitis

Enthesitis and uveitis are common clinical manifestations of SpA. Both conditions have been strongly linked to HLA-B27, and evidence suggests they have shared immune pathways.23-26

McGonagle et al. proposed that the biomechanical properties of uveal structures are similar to musculoskeletal enthesis, both of which are subject to intermittent biomechanical stressing throughout life.25

Biomechanical and microbial factors at disease sites may create a synergistic effect that leads to inflammation.25

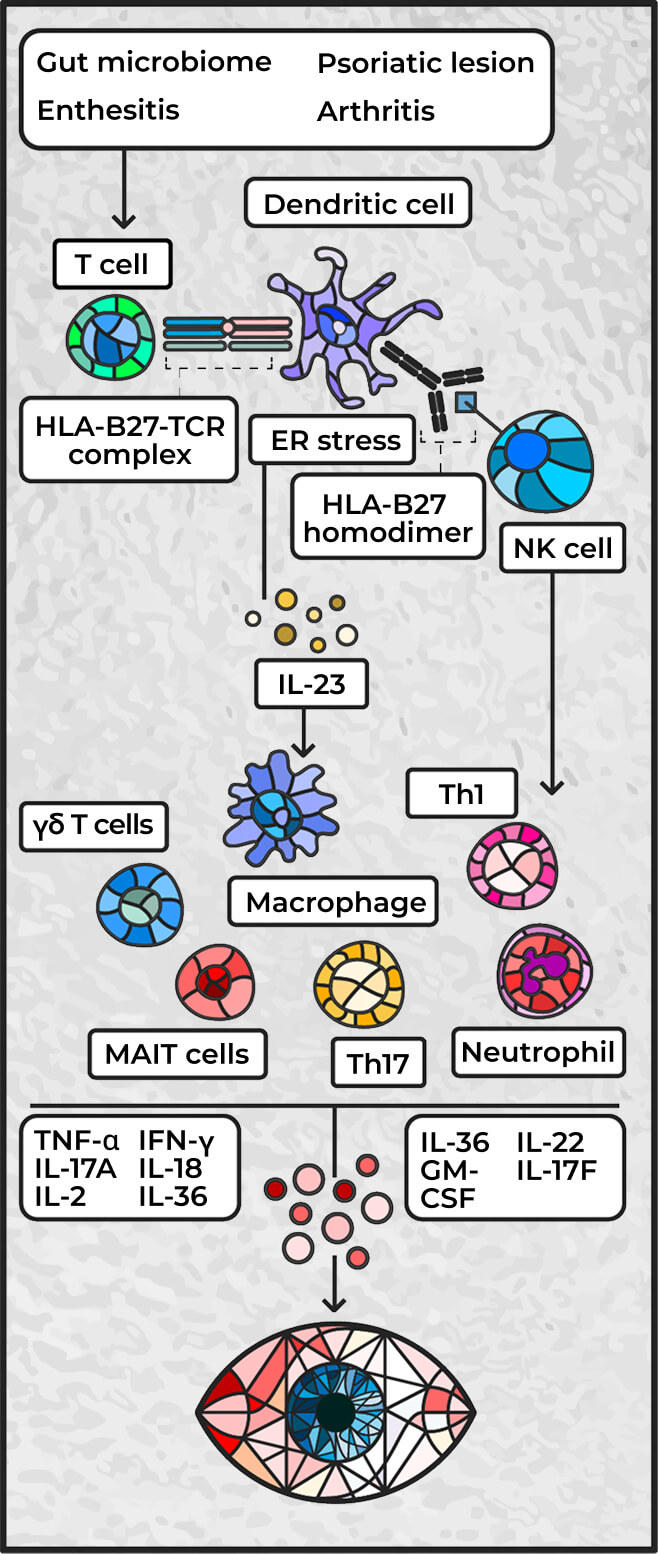

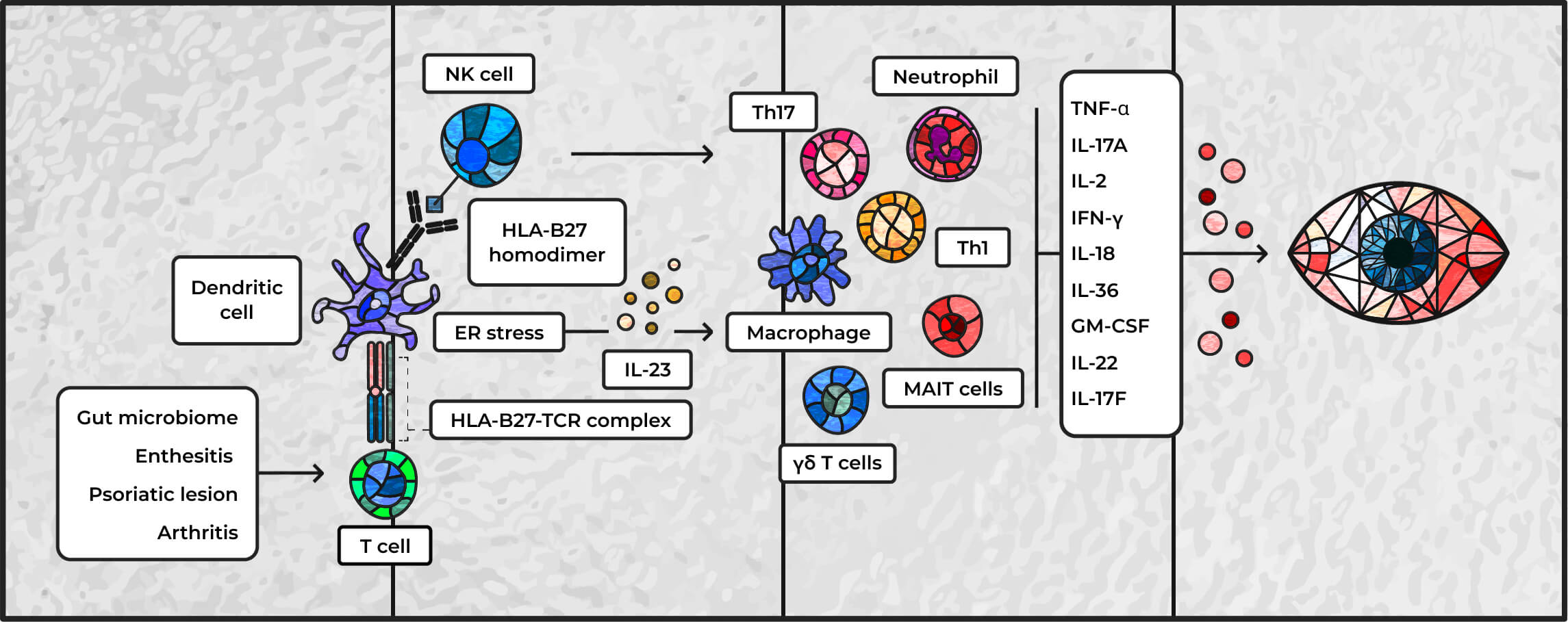

Cytokines play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of autoimmune-related uveitis23,24,27,28

Multiple inflammatory conditions (e.g., IBD, enthesitis, psoriasis, arthritis) have been linked to uveitis and may share inflammatory pathways.3 Key cytokines involved in the pathology of uveitis include IL-17, TNF, and IL-23.3,23,24

TNF=tumor necrosis factor.

Learn more about the role of cytokines in driving inflammation

IL-17

IL-17 is a critical pro-inflammatory cytokine in driving the pathogenesis of autoimmune uveitis.2 In the retina, IL-17 promotes pro-inflammatory cytokine production from retinal pigment epithelial cells, astrocytes, and retinal microglia, potentially leading to vision damage.29

Th17 cells are key mediators of immune dysregulation in the eye. Activation of Th17 cells releases pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-17A, IL-17F, GM-CSF, and IL-22, which perpetuate inflammation through recruitment of additional inflammatory cells.29 Expression of both IL-17A and IL-17F has been shown to be increased in cells collected from patients with AAU compared with healthy controls.24

GM-CSF=granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor.

TNF

TNF has been implicated in chronic inflammation and tissue damage in uveitis.23 In patients with uveitis, increased expression of TNF is found in both the serum and aqueous humor.23

TNF induces the release of secondary cytokines, including IL-6 and IL-8, that are crucial to the inflammatory process.23 In the eye, TNF is key to recruiting leukocytes and other cells whose interaction contributes to the destruction of the blood-retinal barrier.23

IL-23

IL-23 has been implicated in the pathogenesis of autoimmune uveitis, acting via the IL-23/IL-17 pathway.3

IL-23 promotes the expansion and pathogenic activity of Th17 cells, which further promotes the downstream activation of other pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF, IL-17A, and IL-17F.3,30 Dysregulation of this IL-23/IL-17 immunological cascade can disrupt normal cytokine balance, contributing to ocular inflammation.21

Investigate the immunological mechanisms of SpA-related uveitis

Inflammatory etiology of SpA-related uveitis3,24

Adapted from Hysa E, et al. Eur J Clin Invest. 2021;51(8):e13572

ER=endoplasmic reticulum; IFN=interferon; NK=natural killer; MAIT=mucosal-associated invariant T cells; TCR=T-cell receptor; Th=helper T cell.

Managing uveitis poses a complex clinical challenge

Uveitis may serve as a prognostic indicator of worse outcomes in AS patients, and it may also help identify undiagnosed SpA patients sooner, as it may be a patient’s first motivator to seek medical care.16,21,31

The presence of uveitis may also influence treatment decisions for patients with rheumatic diseases.3 Managing uveitis requires a targeted approach, including consideration of the etiology, anatomic site, disease stage, prior treatments, and therapeutic risks.32

A multidisciplinary approach between rheumatologists and ophthalmologists is crucial for appropriate diagnosis and treatment of SpA and uveitis.3,32

Treatment considerations

Managing SpA-associated uveitis should include both managing the acute attack and preventing recurrence.32 Current treatments for uveitis may be local, systemic, or both, and span from anti-inflammatory corticosteroid eyedrops to biologics that target various cytokines.3,32

In the management of SpA, it is important to consider uveitis and its potential impact on treatment considerations.

2022 ASAS-EULAR recommendations

for treatment of axSpA/AS

- If there is a history of recurrent uveitis in patients with axSpA, preference should be given to a monoclonal antibody against TNF; in patients with significant psoriasis, an IL-17 inhibitor may be preferred33

ACR/SAA/SPARTAN October 2019

recommendations for treatment

of axSpA/AS

- TNF inhibitors are conditionally recommended over treatment with other biologics for patients with axSpA and recurrent uveitis34

- Treatment recommendations with IL-17A inhibitors are not clearly defined for patients with uveitis34

Targeted treatment approaches in uveitis should consider the underlying diagnosis, severity, laterality, and comorbidities.32

ACR=American College of Rheumatology; ASAS=Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society; EULAR=European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology; SAA=Spondylitis Association of America; SPARTAN=Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network.

Uncover how mechanism of disease may influence treatment mechanism

Where do we go from here?

Recent research on the etiology of SpA-related uveitis suggests a shared pathobiological pathway between the two diseases.3 Understanding the data behind available treatments targeting these pathways may help in the selection of appropriate therapies to improve patient outcomes.

Learn more about the key cytokines that lead to inflammation

Go deeper: Request an MSL to learn more

TAKE YOUR SEATS IN THE PATHOBIOLOGY LEARNING THEATRE

Uncover how IL-17A and IL-17F work in tandem to inhibit inflammation in SpA

Explore more manifestations of inflammation in new special exhibits

Dive deeper into the role

of cytokines in controlling

inflammation

Examine the link between

PSO and PsA

Become a member of the RheuMuseum and be the first to know about new exhibits

Sign up to stay in the loop on new exhibits about clinical research, important updates, and other educational opportunities.

- Maghsoudlou P, Epps SJ, Guly CM, et al. Uveitis in adults: a review. JAMA. 2025;334(5):419-434. doi:10.1001/jama.2025.4358

- Meng T, Nie L, Wang Y. Role of CD4+ T cell-derived cytokines in the pathogenesis of uveitis. Clin Exp Med. 2025;25(1):49. doi:10.1007/s10238-025-01565-7

- Hysa E, Cutolo CA, Gotelli E, et al. Immunopathophysiology and clinical impact of uveitis in inflammatory rheumatic diseases: an update. Eur J Clin Invest. 2021;51(8):e13572. doi:10.1111/eci.13572

- Guly CM, Forrester JV. Investigation and management of uveitis. BMJ. 2010;341:c4976. doi:10.1136/bmj.c4976

- Agarwal M, Dutta Majumder P, Babu K, et al. Drug-induced uveitis: a review. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68(9):1799-1807. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_816_20

- McCluskey PJ, Towler HM, Lightman S. Management of chronic uveitis. BMJ. 2000;320(7234):555-558. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7234.555

- Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT, et al. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(3):509-516. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.057

- van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, Nurmohamed MT. Management and evaluation of extra-articular manifestations in spondyloarthritis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2012;4(6):413-422. doi:10.1177/1759720X12458372

- Gouveia EB, Elmann D, Morales MS. Ankylosing spondylitis and uveitis: overview. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2012;52(5):742-756

- Wakefield D, Chang JH. Epidemiology of uveitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2005;45(2):1-13. doi:10.1097/01.iio.0000155938.83083.94

- Robinson PC, Claushuis TA, Cortes A, et al. Genetic dissection of acute anterior uveitis reveals similarities and differences in associations observed with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(1):140-151. doi:10.1002/art.38873

- Shamdas M, Bassilious K, Murray PI. Health-related quality of life in patients with uveitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019;103(9):1284-1288. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-312882

- Fabiani C, Vitale A, Orlando I, et al. Impact of uveitis on quality of life: a prospective study from a tertiary referral rheumatology-ophthalmology collaborative uveitis center in Italy. Isr Med Assoc J. 2017;19(8):478-483

- Zhang Z, Griva K, Rojas-Carabali W, et al. Psychosocial well-being and quality of life in uveitis: a review. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2024;32(7):1380-1394. doi:10.1080/09273948.2023.2247077

- Smith WM. Gender and spondyloarthropathy-associated uveitis. J Ophthalmol. 2013;2013:928264. doi:10.1155/2013/928264

- Rademacher J, Poddubnyy D, Pleyer U. Uveitis in spondyloarthritis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2020;12:1759720X20951733. doi:10.1177/1759720X20951733

- Zeboulon N, Dougados M, Gossec L. Prevalence and characteristics of uveitis in the spondyloarthropathies: a systematic literature review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(7):955-959. doi:10.1136/ard.2007.075754

- Maldonado-Ficco H, López-Medina C, Perez-Alamino R, et al. Prevalence and incidence of uveitis in patients with spondyloarthritis: the impact of the biologics era. Data from the international ASAS-COMOSPA study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2025;64(5):2618-2624. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keae536

- de Winter JJ, van Mens LJ, van der Heijde D, et al. Prevalence of peripheral and extra-articular disease in ankylosing spondylitis versus non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18(1):196. doi:10.1186/s13075-016-1093-z

- Miao M, Yan J, Sun Y, et al. The bidirectional association between psoriatic disease and uveitis: an updated meta-analysis. J Cutan Med Surg. Published online April 20, 2025. doi:10.1177/12034754251322764

- Khan MA, Haroon M, Rosenbaum JT. Acute anterior uveitis and spondyloarthritis: more than meets the eye. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17(9):59. doi:10.1007/s11926-015-0536-x

- Muñoz-Fernández S, de Miguel E, Cobo-Ibáñez T, et al. Enthesis inflammation in recurrent acute anterior uveitis without spondylarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(7):1985-1990. doi:10.1002/art.24636

- Jiang Q, Li Z, Tao T, et al. TNF-α in uveitis: from bench to clinic [published correction appears in Front Pharmacol. 2022 Feb 25;13:817235. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.817235]. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:740057. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.740057

- Huang JC, Schleisman M, Choi D, et al. Preliminary report on interleukin-22, GM-CSF, and IL-17F in the pathogenesis of acute anterior uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;29(3):558-565. doi:10.1080/09273948.2019.1686156

- McGonagle D, Stockwin L, Isaacs J, et al. An enthesitis based model for the pathogenesis of spondyloarthropathy: additive effects of microbial adjuvant and biomechanical factors at disease sites. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(10):2155-2159

- Kehl AS, Corr M, Weisman MH. Review: enthesitis: new insights into pathogenesis, diagnostic modalities, and treatment. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(2):312-322. doi:10.1002/art.39458

- Chong WP, Mattapallil MJ, Raychaudhuri K, et al. The cytokine IL-17A limits Th17 pathogenicity via a negative feedback loop driven by autocrine induction of IL-24. Immunity. 2020;53(2):384-397.e5. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2020.06.022

- Dick AD, Tugal-Tutkun I, Foster S, et al. Secukinumab in the treatment of noninfectious uveitis: results of three randomized, controlled clinical trials. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(4):777-787. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.09.040

- Zong Y, Tong X, Chong WP. Th17 response in uveitis: a double-edged sword in ocular inflammation and immune regulation. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2025;68(1):26. doi:10.1007/s12016-025-09038-1

- Bridgewood C, Sharif K, Sherlock J, et al. Interleukin-23 pathway at the enthesis: the emerging story of enthesitis in spondyloarthropathy. Immunol Rev. 2020;294(1):27-47. doi:10.1111/imr.12840

- O'Rourke M, Haroon M, Alfarasy S, et al. The effect of anterior uveitis and previously undiagnosed spondyloarthritis: results from the DUET Cohort. J Rheumatol. 2017;44(9):1347-1354. doi:10.3899/jrheum.170115

- Biggioggero M, Crotti C, Becciolini A, et al. The management of acute anterior uveitis complicating spondyloarthritis: present and future. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:9460187. doi:10.1155/2018/9460187

- Ramiro S, Nikiphorou E, Sepriano A, et al. ASAS-EULAR recommendations for the management of axial spondyloarthritis: 2022 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(1):19-34. doi:10.1136/ard-2022-223296

- Ward MM, Deodhar A, Gensler LS, et al. 2019 Update of the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network recommendations for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(10):1599-1613. doi:10.1002/art.41042