Understanding the importance of early detection and multidisciplinary care in PSO and PsA

PsA=psoriatic arthritis; PSO=psoriasis.

PSO and PsA are closely related conditions that fall under the umbrella of psoriatic disease.1 PSO is a chronic immune-mediated inflammatory skin condition characterized by scaly skin lesions.2

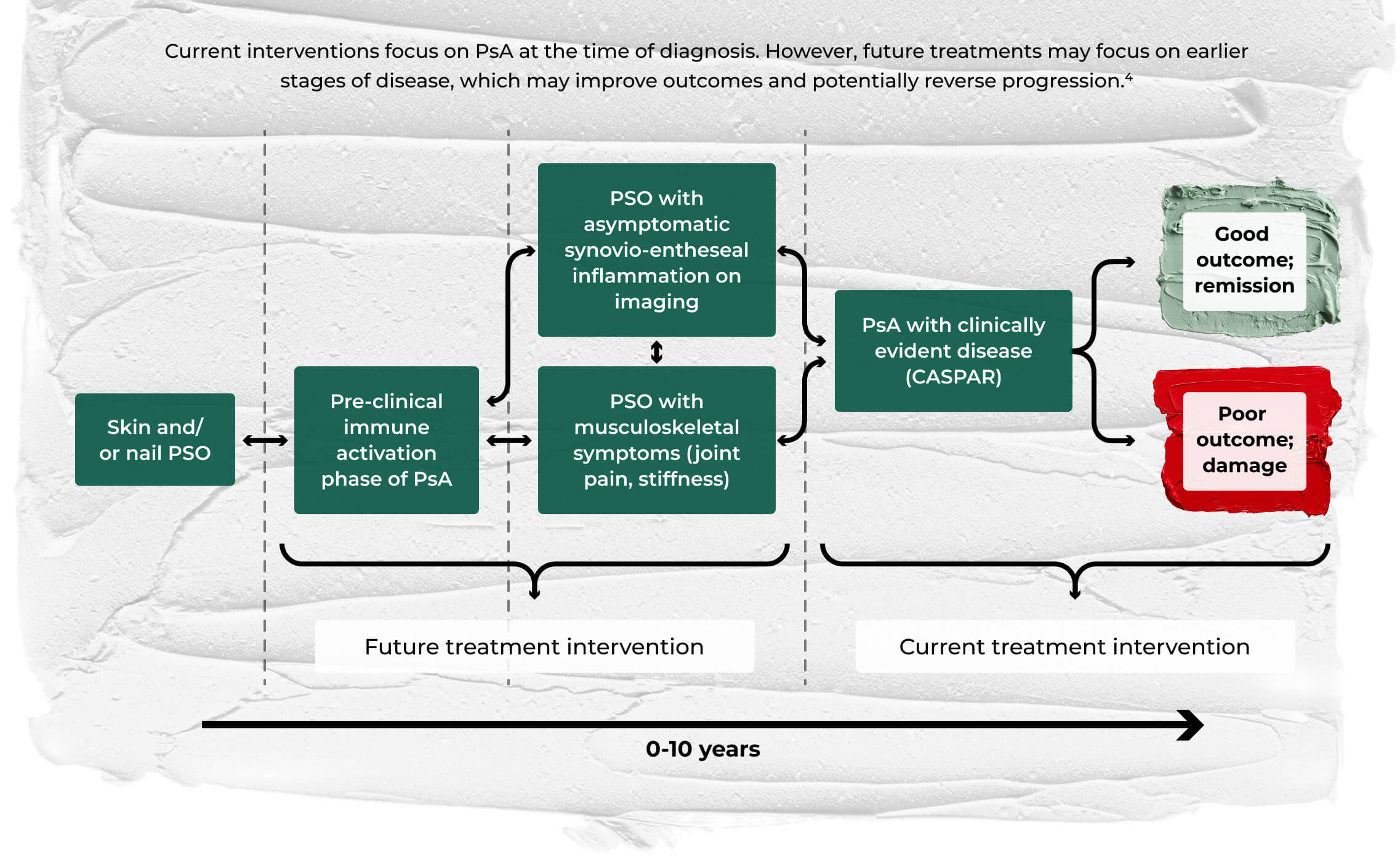

PsA is a chronic inflammatory disease of the skin and musculoskeletal system, characterized by joint pain and other musculoskeletal manifestations.1,3 PsA can begin to develop years before a diagnosis in some cases, with skin symptoms often preceding joint symptoms.4,5

Because PsA has the potential to cause irreversible joint damage and impact quality of life, understanding the relationship between PSO and PsA is important for early and effective management of PsA and improved patient outcomes.5,6

Understanding the link between PSO and PsA

of patients with PSO

will develop PsA9

Cumulative prevalence of PsA in PSO patients increases over time7,8

The annual incidence rate of PsA among patients with PSO ranges from 1.69 to 5.49 per 100 person years, with cumulative prevalence increasing over time.3,7

The timing of PsA onset varies among patients. In most cases (70%), PsA is diagnosed 9–10 years after a diagnosis of PSO. However, in 20% of cases, PsA may be diagnosed simultaneously with PSO. Less than 10% of PsA cases are diagnosed without the presence of PSO.1

PSO and PsA share common genetic and immunological factors

PSO and PsA share common genetic factors that underlie susceptibility to psoriatic disease.2

Both PSO and PsA are immune-mediated inflammatory diseases.10 The inflammatory processes in the skin and joints involve similar pathways, including the overactivation of T cells and increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-17, and IL-23.2

IL=interleukin; TNF=tumor necrosis factor.

Shared inflammatory pathways of PSO and PsA

PSO and PsA share underlying inflammatory processes that contribute to the pathobiology of both conditions.2,11 Several cytokines have been implicated in PSO and other inflammatory diseases, including IL-17, IL-23, and TNF.11,12

Explore the role of key cytokines in driving inflammation in PSO and PsA:

IL-17

The IL-17 family of cytokines consists of six structurally related signaling molecules (IL-17A, IL-17B, IL-17C, IL-17D, IL-17E, and IL-17F) that play important roles in the immune system.13 In PSO and PsA, IL-17A and IL-17F are key inflammatory mediators.14 They cooperate with other inflammatory mediators, including TNF, to amplify inflammatory responses.14

As pleiotropic effector cytokines, both IL-17A and IL-17F promote joint and skin inflammation.11 In PsA, skin lesions and inflamed synovia have similar patterns of IL-17A and IL-17F expression and upregulation.15 IL-17F is found at higher levels in lesional skin of patients with PSO, while IL-17A has been shown to have a more potent pro-inflammatory effect.10

IL-23

IL-23 expression is increased in both psoriatic skin lesions, as well as the synovia of inflamed joints of patients with PsA.16,17

IL-23 plays a pro-inflammatory role by driving the differentiation of naive T cells towards Th17, and stimulating Th17 cells to produce pathogenic cytokines such as IL-17 and IL-22.16,17

The downstream inflammation triggered by the IL-23/IL-17 axis contributes to skin and joint pathology, and may also lead to structural damage, including bone erosion and pathologic bone formation, which are hallmark features of PsA.16-18

TNF

Elevated levels of TNF can be found in psoriatic synovium and skin plaques, as well as entheses, joint, and spine involvement.19,20 TNF plays a central pro-inflammatory role in psoriatic disease, but its function is increasingly understood as synergistic rather than isolated.21,22

In PsA, IL-17 and TNF together amplify inflammatory cytokine expression more potently than either alone.23

In PSO, the therapeutic response to TNF inhibitors may be mediated not solely by direct TNF suppression, but also through downstream effects on IL-17 pathway gene expression.22,23

A closer look at characterization, screening, and treatment of PSO

Comorbidities and disease burden

Due to chronic inflammation, PSO poses an increased risk of cardiovascular comorbidities.25 In addition, PSO is associated with an increased risk of mental health issues and IBD.25

PSO and its associated comorbidities pose a psychological, social, and financial burden to patients.26 These comorbidities, along with patient preferences and varying insurance coverage, may complicate treatment decisions.26

Risk factors for PsA development

The severity of PSO plays a significant role in the progression to PsA, with extensive body surface involvement, and earlier age of PSO diagnosis associated with a higher risk of PsA.5

Specific PSO characteristics, such as nail involvement and PSO in certain locations (scalp, intergluteal, and perianal areas), are also linked to increased PsA risk.4,5

Additionally, certain comorbidities, such as uveitis and type 2 diabetes, are also associated with increased risk of PsA.1,4

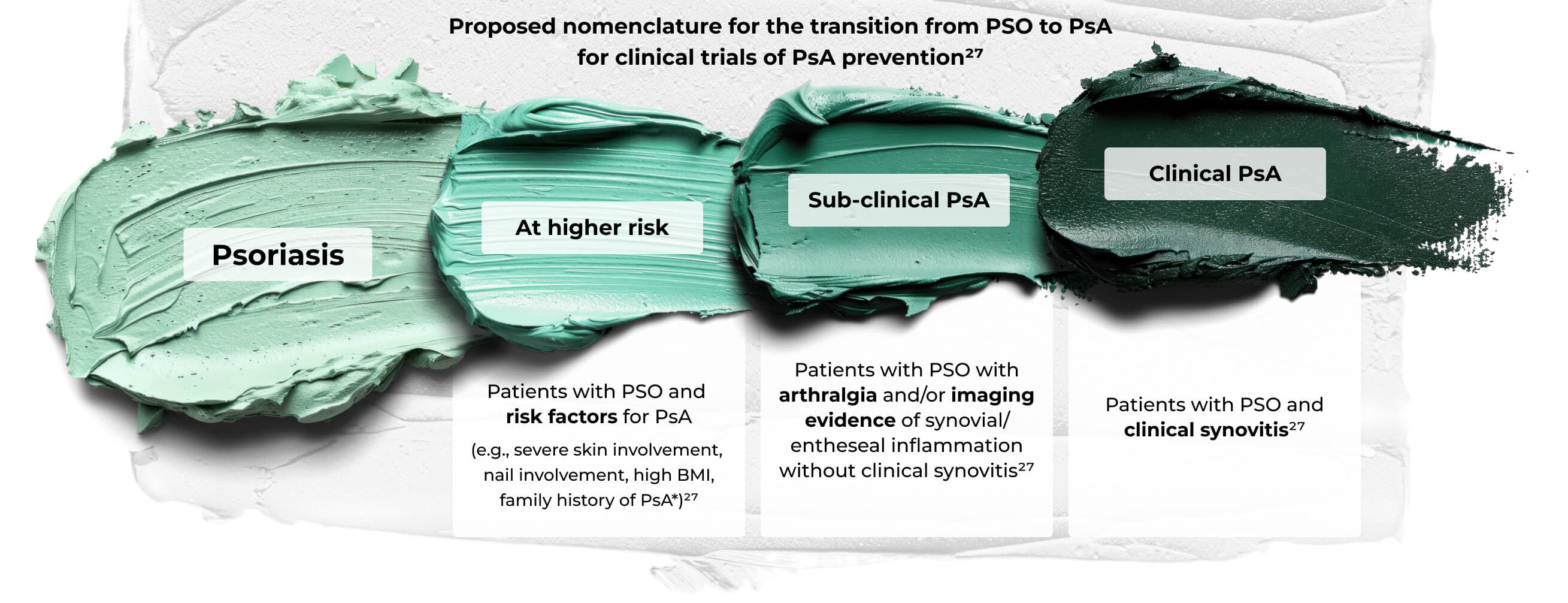

- Clinical progression of PSO to PsA

A three-stage scheme for progression from at risk of PsA to frank PsA. Onset may be variable and could occur quickly in some subjects, for example, after trauma or following infection with a reactive arthritis type onset. Although visuals imply directionality and inevitable progression, some subjects may have spontaneous resolution of PsA, and subjects with arthralgia may regress. Strategies in at-risk people (for example, weight loss in obesity) may lead to reduction of risk. This scheme recognizes the importance of enthesitis in pathophysiology, but for trials of interception suggests the use of synovitis development as an outcome measure since this was by far the most common manifestation of early disease from the accompanying systematic literature reviews.27

*Role of immunogenetics awaits definition.

©Zabotti A, De Marco G, Gossec L, et al. EULAR points to consider for the definition of clinical and imaging features suspicious for progression from psoriasis to psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(9):1162-1170. doi:10.1136/ard-2023-224148. Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Differentiating features of PsA, beyond joint pain

Joint pain often presents as an initial symptom of PsA in patients with PSO.11 Other extra-articular inflammatory features that can provide diagnostic clues for PsA include:

- Enthesitis

- A characteristic feature of PsA, which may be one of its earliest signs, involves inflammation at entheseal sites where tendons and ligaments insert into bone35

- Dactylitis

- Inflammation that causes swelling of the fingers or toes, which can occur in up to 50% of people with PsA35

- Nail symptoms

- Pitting, onycholysis, and hyperkeratosis can precede joint symptoms of PsA4,35

Impact of PSO on quality of life in patients with PsA

People with skin involvement in PsA may experience diminished quality of life compared to patients with only joint involvement.36 Along with physical limitations caused by joint involvement, skin involvement reduces quality of life through emotional distress and discomfort.35 Greater skin involvement is also associated with fatigue, pain, loss of function, and impaired ability to work or complete daily activities.37

Because of this impact on quality of life, it is important to measure patient experience alongside clinical parameters during patient assessments.38 One measurement tool is the Psoriasis Symptoms and Impacts Measure (P-SIM), which was developed to capture patients’ experience of the impacts of PSO with a daily 14-item electronic diary and may be useful in assessing treatment outcomes.39

Management considerations for PSO

Treatment options for PSO vary based on a variety of factors, including comorbidities, patient preference, and disease severity.26

PSO disease severity can be classified by extent of skin involvement

-

Mild PSO <3%–5% of body surface area25 -

Moderate PSO 3%–10% of body surface area25 -

Severe PSO ≥10% of body surface area25

Mild-to-moderate PSO may be adequately treated with topical medications or phototherapy.40 Moderate-to-severe disease may be treated with biologics, either alone or alongside other topical or systemic medications.40

Consider the value of a multidisciplinary approach to treating PSO and PsA

While many PsA patients are managed by rheumatologists alone, the patient burden of skin disease highlights the importance of multidisciplinary management.36

Dermatologists play a key role in identifying early signs of PsA. Monitoring for signs of joint or arthritic involvement in patients with PSO, along with knowledge of PsA screening, diagnosis, and treatment, can help dermatologists proactively address PSO progression to clinical PsA.35

Dermatologists should consider early referral of suspected PsA to a rheumatologist where possible, especially if PsA manifestations do not respond to treatment.35 This multidisciplinary approach ensures comprehensive management of both skin and joint symptoms and can improve treatment outcomes for both skin and musculoskeletal symptoms.41

Early detection of signs of PsA is crucial, as a greater than 6-month delay in diagnosis can contribute to poor outcomes.4

- Pathway to earlier treatment of PsA in patients with PSO4

©Pennington SR, FitzGerald O. Early origins of psoriatic arthritis: clinical, genetic and molecular biomarkers of progression from psoriasis to psoriatic arthritis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:723944. doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.723944. Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

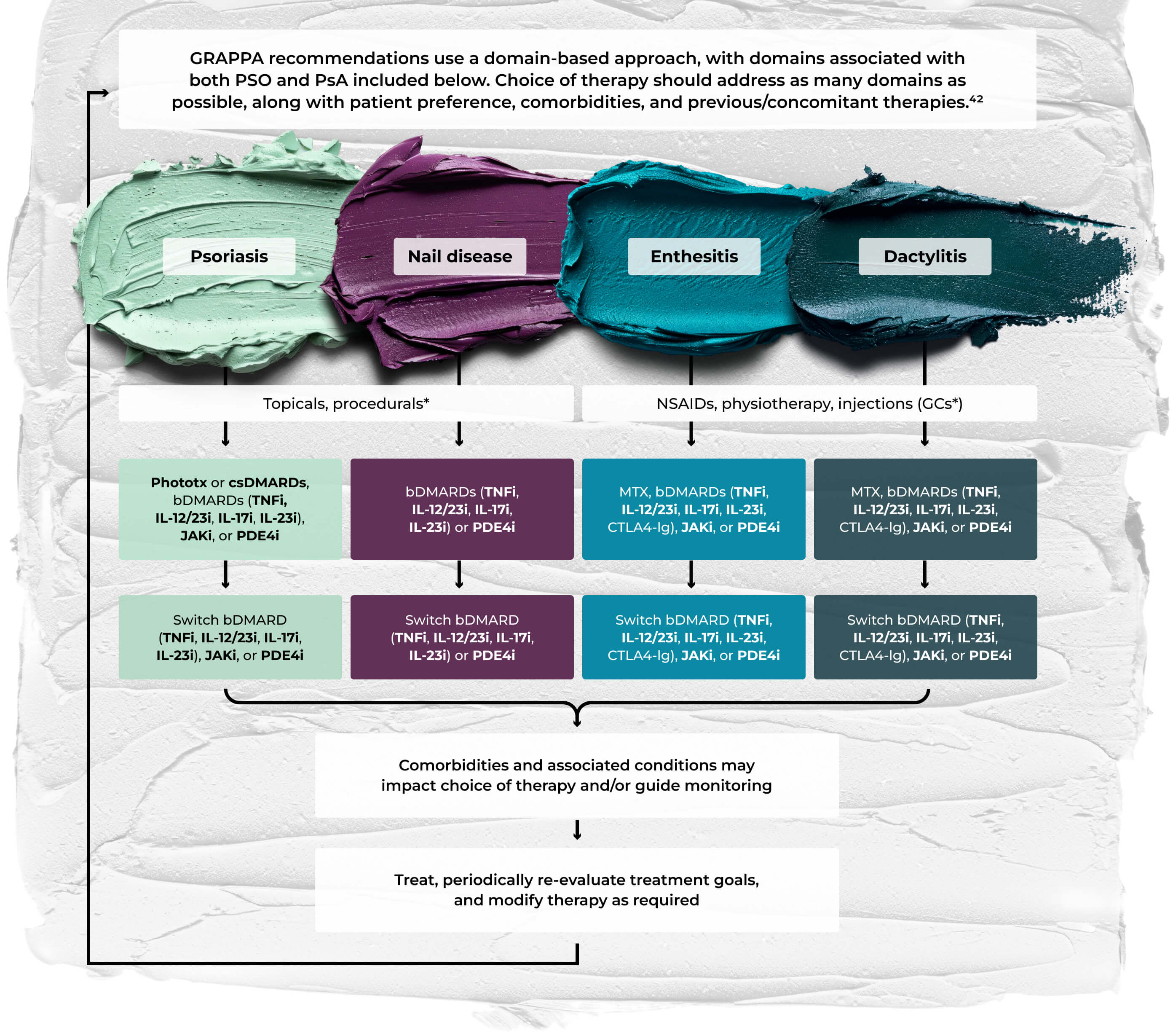

- GRAPPA recommendations for patients with PsA42

Does not include all possible domains of PsA in GRAPPA treatment schema; other domains include peripheral arthritis, axial disease, IBD, and uveitis. Bold text indicates a strong recommendation, standard text a conditional recommendation. Asterisks indicate a conditional recommendation based on data from abstracts only. bDMARD=biologic DMARD; csDMARD=conventional synthetic DMARD; CTLA4-Ig=CTLA4–immunoglobulin fusion protein; GC=glucocorticoid; JAKi=Janus kinase inhibitor; PDE4i=phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor; phototx=phototherapy; TNFi=TNF inhibitor.

©Coates LC, Soriano ER, Corp N, et al. Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA): updated treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis 2021 [published correction appears in Nat Rev Rheumatol. December 2022;18(12):734. doi: 10.1038/s41584-022-00861-w]. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2022;18(8):465-479. doi:10.1038/s41584-022-00798-0. Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

LECTURE SERIES WITH DR. SAAKSHI KHATTRI

Comprehensive care for PSO requires collaboration between dermatologists and rheumatologists3,36

“When I have a patient in my practice who I’m seeing for psoriasis, I’m always acutely aware of psoriatic arthritis, just given the data that says many psoriasis patients will develop PsA.35

“Frequently, there’s a delay in diagnosing PsA, and even 6 months of delay in diagnosis can result in irreversible joint damage.4 So, in the dermatology space, when I have a psoriasis patient, I’m always thinking PsA in the back of my head.”

Watch Dr. Khattri’s lecture on clinical manifestations of PsA.

TAKE YOUR SEATS IN THE PATHOBIOLOGY LEARNING THEATRE

Uncover how IL-17A and IL-17F work in tandem to drive inflammation in SpA

Explore more manifestations of inflammation in new special exhibits

Dive deeper into the role

of cytokines in controlling

inflammation

Explore the effects of

uveitis as a manifestation

of inflammation

Become a member of the RheuMuseum and be the first to know about new exhibits

Sign up to stay in the loop on new exhibits about clinical research, important updates, and other educational opportunities.

- Huo AP, Liao PL, Leong PY, et al. From psoriasis to psoriatic arthritis: epidemiological insights from a retrospective cohort study of 74,046 patients. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1419722. doi:10.3389/fmed.2024.1419722

- Zalesak M, Danisovic L, Harsanyi S. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis-associated genes, cytokines, and human leukocyte antigens. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024;60(5):815. doi:10.3390/medicina60050815

- Lindberg I, Lilja M, Geale K, et al. Incidence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with skin psoriasis and associated risk factors: a retrospective population-based cohort study in Swedish routine clinical care. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100(18):adv00324. doi:10.2340/00015555-3682

- Pennington SR, FitzGerald O. Early origins of psoriatic arthritis: clinical, genetic and molecular biomarkers of progression from psoriasis to psoriatic arthritis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:723944. doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.723944

- Busse K, Liao W. Which psoriasis patients develop psoriatic arthritis? Psoriasis Forum. 2010;16(4):17-25

- Urruticoechea-Arana A, Benavent D, León F, et al. Psoriatic arthritis screening: a systematic literature review and experts’ recommendations. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0248571. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0248571

- Christophers E, Barker JN, Griffiths CE, et al. The risk of psoriatic arthritis remains constant following initial diagnosis of psoriasis among patients seen in European dermatology clinics. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24(5):548-554. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03463.x

- Merola JF, Tian H, Patil D, et al. Incidence and prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis stratified by psoriasis disease severity: retrospective analysis of an electronic health records database in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(4):748-757. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.09.019

- Ogdie A, Weiss P. The epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015;41(4):545-568. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2015.07.001

- Navarro-Compán V, Puig L, Vidal S, et al. The paradigm of IL-23-independent production of IL-17F and IL-17A and their role in chronic inflammatory diseases. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1191782. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1191782

- López-Medina C, McGonagle D, Gossec L. Subclinical psoriatic arthritis and disease interception-where are we in 2024? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2025;64(1):56-64. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keae399

- Munera-Campos M, Ballesca F, Carrascosa JM. Paradoxical reactions to biologic therapy in psoriasis: a review of the literature. Reacciones paradójicas de los tratamientos biológicos utilizados en psoriasis: revisión de la literatura. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2018;109(9):791-800. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2018.04.003

- Brembilla NC, Senra L, Boehncke WH. The IL-17 family of cytokines in psoriasis: IL-17A and beyond. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1682. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.01682

- Glatt S, Baeten D, Baker T, et al. Dual IL-17A and IL-17F neutralisation by bimekizumab in psoriatic arthritis: evidence from preclinical experiments and a randomised placebo-controlled clinical trial that IL-17F contributes to human chronic tissue inflammation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(4):523-532. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212127

- Ritchlin CT, Kavanaugh A, Merola JF, et al. Bimekizumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results from a 48-week, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging phase 2b trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10222):427-440. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33161-7

- Boutet MA, Nerviani A, Gallo Afflitto G, et al. Role of the IL-23/IL-17 axis in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: the clinical importance of its divergence in skin and joints. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(2):530. doi:10.3390/ijms19020530

- Sakkas LI, Bogdanos DP. Are psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis the same disease? The IL-23/IL-17 axis data. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16(1):10-15. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2016.09.015

- Gravallese EM, Schett G. Effects of the IL-23-IL-17 pathway on bone in spondyloarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2018;14(11):631-640. doi:10.1038/s41584-018-0091-8

- Addimanda O, Possemato N, Caruso A, et al. The role of tumor necrosis factor-α blockers in psoriatic disease. Therapeutic options in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2015;93:73-78. doi:10.3899/jrheum.150642

- Silvagni E, Missiroli S, Perrone M, et al. From bed to bench and back: TNF-α, IL-23/IL-17A, and JAK-dependent inflammation in the pathogenesis of psoriatic synovitis. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:672515. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.672515

- Schett G, Rahman P, Ritchlin C, et al. Psoriatic arthritis from a mechanistic perspective. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2022;18(6):311-325. doi:10.1038/s41584-022-00776-6

- Blauvelt A, Chiricozzi A. The Immunologic role of IL-17 in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis pathogenesis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;55(3):379-390. doi:10.1007/s12016-018-8702-3

- Noack M, Beringer A, Miossec P. Additive or synergistic interactions between IL-17A or IL-17F and TNF or IL-1β depend on the cell type. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1726. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.01726

- Zaba LC, Suárez-Fariñas M, Fuentes-Duculan J, et al. Effective treatment of psoriasis with etanercept is linked to suppression of IL-17 signaling, not immediate response TNF genes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(5):1022-10.e395. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.08.046

- Armstrong AW, Read C. Pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatment of psoriasis: a review. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1945-1960. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4006

- Feldman SR, Goffe B, Rice G, et al. The challenge of managing psoriasis: unmet medical needs and stakeholder perspectives. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2016;9(9):504-513

- Zabotti A, De Marco G, Gossec L, et al. EULAR points to consider for the definition of clinical and imaging features suspicious for progression from psoriasis to psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(9):1162-1170. doi:10.1136/ard-2023-224148

- Coates LC, Bukhari M, Chan A, et al. Enhancing current guidance for psoriatic arthritis and its comorbidities: recommendations from an expert consensus panel. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2025;64(2):561-573. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keae172

- Iragorri N, Hazlewood G, Manns B, et al. Psoriatic arthritis screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58(4):692-707. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/key314

- Husni ME, Meyer KH, Cohen DS, et al. The PASE questionnaire: pilot-testing a psoriatic arthritis screening and evaluation tool. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(4):581-587. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.04.001

- Ibrahim GH, Buch MH, Lawson C, et al. Evaluation of an existing screening tool for psoriatic arthritis in people with psoriasis and the development of a new instrument: the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) questionnaire. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27(3):469-474

- Gladman DD, Schentag CT, Tom BD, et al. Development and initial validation of a screening questionnaire for psoriatic arthritis: the Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen (ToPAS). Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(4):497-501. doi:10.1136/ard.2008.089441

- Tinazzi I, Adami S, Zanolin EM, et al. The early psoriatic arthritis screening questionnaire: a simple and fast method for the identification of arthritis in patients with psoriasis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51(11):2058-2063. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kes187

- Audureau E, Roux F, Lons Danic D, et al. Psoriatic arthritis screening by the dermatologist: development and first validation of the 'PURE-4 scale'. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(11):1950-1953. doi:10.1111/jdv.14861

- Mease PJ, Armstrong AW. Managing patients with psoriatic disease: the diagnosis and pharmacologic treatment of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis. Drugs. 2014;74(4):423-441. doi:10.1007/s40265-014-0191-y

- Pitzalis C, Myall N, Dey M, et al. Severity of skin disease strongly correlates with quality of life in people with psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatol Int. 2025;45(2):39. doi:10.1007/s00296-025-05791-w

- Mease PJ, Karki C, Palmer JB, et al. Clinical and patient-reported outcomes in patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) by body surface area affected by psoriasis: results from the Corrona PsA/Spondyloarthritis Registry. J Rheumatol. 2017;44(8):1151-1158. doi:10.3899/jrheum.160963

- Warren RB, Gottlieb AB, Merola JF, et al. Psychometric validation of the Psoriasis Symptoms and Impacts Measure (P-SIM), a novel patient-reported outcome instrument for patients with plaque psoriasis, using data from the BE VIVID and BE READY Phase 3 trials. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11(5):1551-1569. doi:10.1007/s13555-021-00570-4

- Gottlieb AB, Ciaravino V, Cioffi C, et al. Development and content validation of the Psoriasis Symptoms and Impacts Measure (P-SIM) for assessment of plaque psoriasis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10(6):1255-1272. doi:10.1007/s13555-020-00434-3

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(4):1029-1072. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.057

- Ochôa Matos C, Cunha-Santos F, Silva A, et al. Rheumatology and dermatology multidisciplinary clinic improves diagnostic precision and treatment decisions in patients suspected or diagnosed with psoriatic arthritis. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2024;17:6143-6151. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S486029

- Coates LC, Soriano ER, Corp N, et al; and the GRAPPA Treatment Recommendations domain subcommittees. Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA): updated treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis 2021. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2022;18(8):465-479. doi:10.1038/s41584-022-00798-0